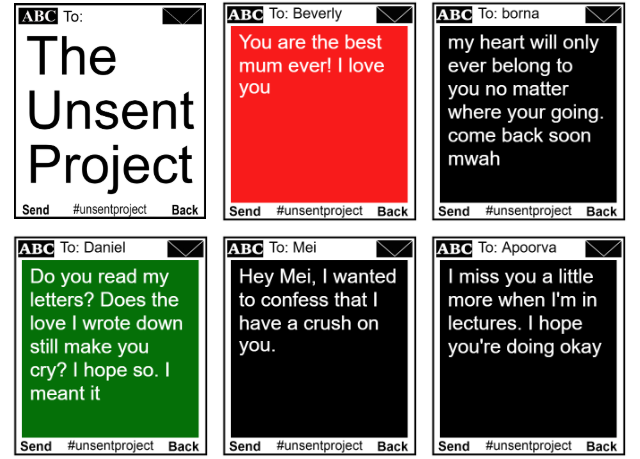

The Unsent Project: Decoding Secrets of Untold Stories

We are living in an era of digital ghosts where our communication is defined as much by what we delete as what we send. It seems complex at first. In fact, the act of typing a message and then backspacing is a modern psychological ritual that everyone performs, but nobody really documents efficiently.

This article isn’t just about looking at sad texts. Rather, it is about dissecting the digital debris of human relationships. It is important to examine these archives’ function, which reveals something raw about the human condition.

By examining The Unsent Project, we can begin to map the cartography of modern heartbreak and the silence that follows it.

The Unsent Project: Historical Origins and Cultural Relevance

Confession is an ancient impulse that has recently found new screens to project onto. In fact, long before screenshots and blue bubbles, people were screaming into the void in other ways.

Think about PostSecret in the early 2000s. Back then, Frank Warren handed out postcards and asked strangers to share their secrets. As a result, the mailbox became a confessional booth.

Then came apps like Whisper and Yik Yak. These turned the geographic proximity of users into a localized gossip stream. It shifted the culture. Now, we moved from private diaries locked with a key to public broadcasts shielded by anonymity.

This transition changed the expectation of privacy itself. We started expecting our secrets to be consumed by an audience. This created a specific cultural moment where “unsent” messages became a genre of literature.

Essentially, it is performance art for the lonely. The audience for this is not merely voyeurs. It might be anyone who has ever felt the sting of a conversation that ended too soon. In fact, even you are part of the dataset.

Origins and Scope of The Unsent Project

This specific archive began as an art concept by Rora Blue, intended to visualize the colors people associate with their first loves. It started small, with a localized attempt to connect color theory with emotional recall.

But the internet took a small idea and blew it up into a global phenomenon. The stated mission shifted from pure art to a form of collective therapy. It claims to have tens of thousands of submissions.

Verifying these numbers is a nightmare because there is no independent audit of the backend database. We just see what gets posted or printed on stickers.

The distinction here is critical. An archive implies a systematic, neutral collection of records. Also, an art project implies curation, selection, and aesthetic bias.

Methodology and Data

The following are the methodology and data with which the Unsent Project works:

1. Data Collection and Provenance

The collection mechanism is deceptively simple, which is exactly where the data integrity starts to fall apart. It is usually an open form. Basically, you type a name and message, and then pick a color. There is no verification that you are who you claim to be. Also, you do not know whether the person you are writing to even exists.

It is the honor system applied to the internet, which is a terrifying concept where provenance is nonexistent. Also, it is not possible to find out whether a submission is a genuine heartfelt confession from a teenager in Ohio or a bot farm testing text generation.

This lack of gatekeeping is a feature, not a bug. Actually, it lowers the barrier to entry. Moreover, it is a hurdle to analysis. If you were to ask the maintainers questions, you would need to ask about the timestamp metadata.

You should ask if they filter out duplicates or if they trace IP addresses to prevent spamming. Without that transparency, we are looking at a dataset with inaccuracies. It is raw noise mixed with a genuine signal.

| Feature | Academic Survey | Social Media Scraping | The Unsent Project |

| Verification | High (ID checks) | Low (Public profiles) | None (Open form) |

| Consent | Explicit/Signed | Implied by TOS | Ambiguous |

| Structure | Rigid Questions | Unstructured Text | Semi-structured (Text + Color) |

| Context | Demographics known | Profile linkage | Context stripped completely |

2. Tagging, Categorization, and Color Taxonomy

The core novelty here is the color association, but how do we actually categorize this data? It relies on self-selection. Essentially, the user decides that “anger” appears “red” or that “sadness” looks like “blue.”

This is manual tagging at its most subjective. A more rigorous approach would be supervised machine learning, where a model is trained to recognize sentiment and see if it aligns with the chosen color.

However, all we have are crowd-sourced labels. The strength of this approach lies in its ability to capture the user’s perception of their emotion, which is valuable. Meanwhile, a weakness is that human beings are mostly inconsistent.

For instance, one person’s “neon green” is envy, while another’s “neon green” is disgust. It creates a taxonomy that is visually striking but analytically chaotic.

In fact, if you try to sort this database, you aren’t sorting by objective metrics. Rather, you are sorting by vibes. It makes quantitative analysis difficult because the variables (the colors) are not standardized. They are fluid definitions based on personal experiences and perceptions.

3. Analytic Methods and Limitations

If this text is run through typical NLP (Natural Language Processing) tools, the machine would stop. This is because of the following reasons:

- These messages are short.

- They are context-dependent.

- They are full of slang, typos, and inside jokes.

In general, topic modeling algorithms like LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation) struggle with short texts because there isn’t enough word co-occurrence to form solid clusters.

Meanwhile, sentiment analysis is even riskier. Sarcasm is the default language of the heartbroken internet user. For instance, a message saying “I hope you have a great life!“ could be genuine well-wishing, or it could be a passive-aggressive curse.

In this case, an algorithm cannot distinguish between them without tonal markers. Moreover, cultural idioms also skew the data. A phrase that means love in one subculture might signal disrespect in another. To trust any analysis of this data, we need transparency metrics.

Ethics, Privacy, and Moderation

The following are some of the major factors related to ethics, privacy, and moderation:

1. Consent and Anonymity Practices

Primarily, explicit consent usually involves a signed form and a clear understanding of how data will be used. In this scenario, the sender consents by clicking the submit button.

But what about the recipient? The person named in the message never agreed to have their name on a website or a sticker. Of course, “First Name” is not a unique identifier. However, if a message references a specific location, date, and a name, re-identification becomes really easy.

Obviously, it is possible to triangulate identities with little information. The practice here relies on “security through obscurity,” which means hoping the sheer volume of data hides the individual.

2. Harm Minimization and Moderation Protocols

What happens when the messages turn dark? It leads to doxxing, threats, and self-harm. In fact, a platform hosting user-generated content has a moral (and legal) obligation.

Moreover, harm minimization requires 24/7 moderation. You cannot rely on automated filters alone because trolls are creative. Also, they will find ways to circumvent keyword lists by spelling out slurs or threats.

In addition, reporting workflows should be visible. If you see a message that threatens violence, you need a big red button to click. If that button doesn’t exist, or if it leads to a dead email inbox, the platform is negligent.

3. Legal and Regulatory Considerations

Data retention is the overlooked legal part that actually matters.

- How long is this data kept?

- Who owns it?

- If the project shuts down, does the data get sold?

Basically, these are jurisdictional nightmares. In Europe, the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) gives users the “right to be forgotten.”

Does this project have a mechanism to honor that? If you submit a message at 16 and regret it at 24, can you get it deleted? The takedown rights need to be explicitly stated in the privacy documentation.

Most art projects operate in a legal blind spot, assuming they are too small to be sued. But as they scale, that immunity evaporates.

In fact, documentation needs to be public-facing and written in plain English, not legalese. It must say exactly who controls the servers and what jurisdiction they are in. Without that, users are throwing their secrets into a black box with no legal recourse.

Analysis of The Unsent Project Findings

The following points analyze the findings of the Unseen Project:

1. The Color Taxonomy

The project suggests a mapping where colors equal feelings.

- Red typically maps to anger or passion.

- Blue maps to sadness or depression.

- Yellow is often nostalgia or friendship.

However, this mapping is not rigid. You have to validate these mappings by reading the text. When you look closely, you see the cultural bias in color meaning. In the West, blue is sad. In other cultures, white might be the color of mourning.

In fact, the project is heavily skewed toward Western color psychology. There are potential misclassifications everywhere. A user might pick pink because it was the color of the shirt the person wore, not because they feel “playful” or “romantic.”

The visual data is contaminated by aesthetic choices that have nothing to do with emotion. The system is trying to force a chaotic spectrum of human feeling into a Crayola box. It simplifies the data for Instagram, but it complicates the actual understanding of the emotion.

2. Patterns, Themes, and Narrative Structures

Despite the chaos, patterns emerge, and narrative structures repeat themselves. The most common motif is the “non-apology apology,” where the sender admits fault but frames it as inevitable.

Then there is the “closure seeking” motif, which is usually a lie. The sender doesn’t want closure, but wants contact.

In fact, there are clusters of regret. Temporal patterns are fascinating if you could access the timestamps. You would likely see spikes late at night, the classic “2 AM text” phenomenon. You would see spikes around holidays, specifically Valentine’s Day and Christmas, the high holy days of loneliness.

Demographic signals are harder to parse without explicit data, but the language mostly tends to skew young. The slang, the references to school, and the specific cadence of the phrasing point to a Gen Z and younger Millennial cohort.

3. Risks of Overinterpretation

One must be careful not to read too much into this. This is because aggregate statistics can mislead. Just because 40% of the messages are blue doesn’t mean 40% of the population is clinically depressed. Rather, it means 40% of the people who chose to visit a website about unsent texts felt like picking blue that day.

That is a selection bias. The people contributing to this archive are self-selecting for heartbreak or unresolved conflict. You don’t write an unsent letter to your dentist about a successful cleaning. Rather, you write it to the ex who ruined your summer.

Therefore, the findings will always skew negative. Presenting these findings responsibly means acknowledging that this is a museum of the worst moments, not a representative sample of all human communication. Essentially, sensationalism is the enemy of truth here.

Practical Implications and Recommendations

The following are some of the major practical implications and recommendations regarding the Unseen Project:

1. For Researchers

If you are an academic, do not just scrape the website and run a Python script. You need a minimum transparency checklist. Ask for the raw data structure and the removal rate.

If you cannot verify the source, you cannot publish the findings as fact. You have to frame it as an analysis of a “digital cultural artifact,” and not a sociological study of relationships.

Replication is impossible because the database changes every day. Validation steps must include cross-referencing with other confession platforms to see if the themes hold up. Treat it like radioactive material; handle it with extreme caution and protective gear.

2. For Creators and Curators

It is not merely about aesthetics. In fact, the best practices for consent need to be front and center. You need clear community guidelines that are enforced, not just suggested.

So, design the platform to reduce harm. Also, maybe add a “cooling off” period where a user submits a message, but it doesn’t go live for 24 hours.

Moreover, give them a chance to delete it. Increase participant agency by allowing them to tag their own posts with “trigger warnings” rather than relying on moderators to catch everything.

3. For Readers and Participants

Read responsibly, and do not hunt for people you know. Most readers and participants try to see their names there. However, interpreting these excerpts requires distance. Remember that you are seeing one side of a story, which is usually written in a moment of high emotion.

So, if you find something that violates your privacy, do the following:

- Request removal

- Document the URL

- Take screenshots. Do not engage with the platform if they ignore you; go to the host. You have to be your own advocate in the digital wild west.

Wrapping Up

The fascination with these archives reveals a desperate need for connection in a world that is fragmented. Understand that your secret pain is not unique. Also, voyeurism comes with a price.

Hence, greater transparency is required from the people who are collecting secrets. Also, they must show higher ethical standards for how this data is displayed and monetized. Moreover, research rigor is necessary, which does not merely accept the data at face value but questions its origin. The Unsent Project ultimately serves as a mirror.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): The Unsent Project

The following are some FAQs regarding The Unseen Project:

An archive is about preservation, history, and neutrality. It wants to keep the record straight. Meanwhile, an art project is about expression, curation, and provoking a reaction. It aims to evoke a feeling. The Unsent Project blurs the line, but it leans heavily toward art because of the lack of rigorous metadata.

Practical steps include:

a) Requesting raw counts from the database administrator.

b) Look for public statements with timestamps to see if the growth trajectory makes sense.

Honestly, no. True anonymity is almost impossible online. They are “pseudonymous” at best. While they might redact the last name, the combination of “First Name + Message Content + Color Context” mostly reveals who sent it to the person receiving it.

If your message appears, do the following:

a) Go to the “Contact” or “Legal” section of the site immediately.

b) Submit a formal takedown request.

c) Provide the specific URL and the text of the message.

d) If they have a DMCA form, use it.

e) Document everything.

If they don’t respond, you might have to contact the web host directly to report a privacy violation.

Read Also: